Chautauqua intersection is being discussed by Caltrans and Los Angeles. Cars in the near lane are supposed to turn onto West Channel Road, but often cut the line on cars in the far lane.

Representatives from Caltrans and the L.A. Department of Transportation hear more complaints about traffic flow at the intersection of Pacific Coast Highway, Chautauqua and W. Channel Road than any other intersection in the area.

The major problem involves motorists who drive down Chautauqua to reach PCH or to make a U-turn onto W. Channel Road. This feeder road was never designed for efficiency and causes a logistical nightmare throughout the day.

At the Pacific Palisades Community Council meeting on October 22, Tim Fremaux, an LADOT senior transportation engineer, discussed changes under consideration for the Chautauqua/PCH intersection.

He said his department had spoken to Caltrans about the intersection (which is under both jurisdictions), and he admitted that it has challenges, dating back to when Chautauqua was paved in the 1920s

Council members made it clear that residents somehow want a solution to the challenges drivers face as they go downhill on Chautauqua towards PCH. There are two lanes, but only one lane is designated for a left turn onto southbound PCH and this often causes Chautauqua traffic to back up for blocks.

In response, some motorists go down the less-crowded left lane (which is designated for a U-turn onto W. Channel Road), and then skip the line, forcing their way into the right lane when the light turns green in order to reach PCH.

This is dangerous and it causes traffic to jam up even more in that right lane. This is especially aggravating to drivers in the right lane who abide by the spirit of the road, especially because they know they will have to wait about three minutes for another green light if they don’t reach the PCH interaction.

One resident asked if perhaps a camera and fines could be implemented at that intersection in order to penalize drivers who try to enter PCH from the left lane. Fremaux told him, “No, that program (traffic cameras) was terminated,” because there were problems in court with the whole process.

Resident Lou Kamer, who has worked tirelessly to get a left-hand turn signal at another deadly intersection in the Palisades (Sunset at Chautauqua), asked if bollards could be placed between the two lanes, higher up the street, so that people would be aware that the left-hand-turn lane was supposed to turn onto West Channel.

Fremaux said he’d look into that suggestion.

Resident Katherine Waltzer suggested a short term fix for the corner at PCH and Chautauqua that often leads to backups during rush hour.

Another traffic-flow problem is caused by motorists on westbound West Channel who want to enter PCH at the signal, but who pull into the far right lane and then realize it’s a dedicated right-hand turn up to Chautauqua. They then have to wait for a green light, but meanwhile block the lane for people who are headed for Chautauqua.

Kamer also suggested putting bollards between the center and the right lane on West Channel, so that people unfamiliar with the area would be alerted sooner.

The PPCC’s youth representative, Zennon Ulyakcrow, told the board that he rides the Big Blue Bus, and that the bus cannot turn from West Channel onto Chautauqua because of the turning radius. So the driver must go down Entrada and turn right onto PCH before turning right onto Chautauqua to go into the Palisades.

He wondered if the LADOT had ever looked at making Entrada a one-way street as a way to clarify traffic patterns.

Fremaux said that was an interesting consideration. He listened to additional comments from residents and said that the City would continue to consult with Caltrans representatives.

Fremaux also introduced a plan under consideration: Taking the two right-hand-turn lanes going north on PCH that allow people to turn onto West Channel or onto Chautauqua and converting them into one right-hand-turn lane.

People from the community acknowledged that it might make sense, but that when traffic backs up on PCH, most residents use the inner right-hand-turn lane as a way to access Chautauqua. Doing away with one right-hand turn was dismissed as one that wouldn’t solve traffic problems.

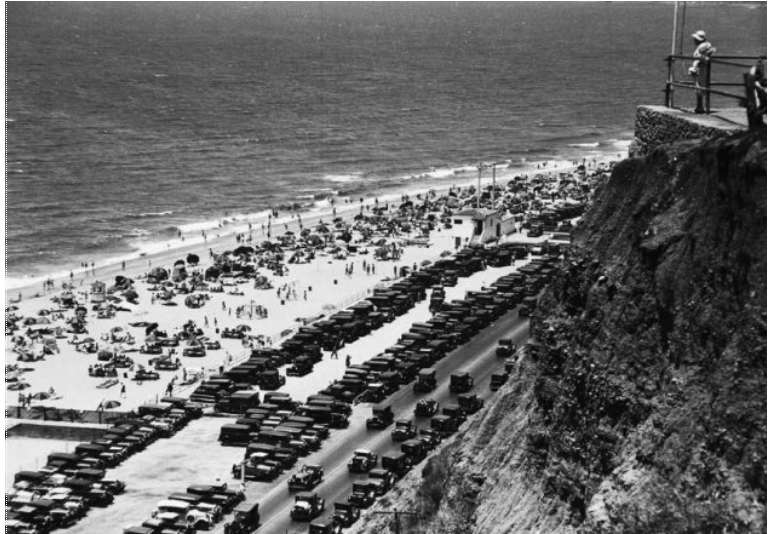

The challenges at Chautauqua and PCH go all the way back to the late 1920s, just a few years after Pacific Palisades was founded. In 1929, Roosevelt Highway (now PCH) was dedicated as a paved highway all the way from Santa Monica to Oxnard, via Malibu. And concurrently, the traffic started increasing past Santa Monica Canyon.

According to a 2012 KCET feature (“From Roosevelt Highway to the 1: A Brief History of Pacific Coast Highway”), the road was renamed Pacific Coast Highway in much of Southern California in 1941. The highway, which had initially met transportation needs, was already feeling strained in the 1950s and a new Pacific Coast Freeway was envisioned.

“Some cities, like Laguna Beach and Costa Mesa, fought the plan. Others sought to modify it: Santa Monica officials proposed a seven-mile causeway stretching from Topanga Canyon to the Santa Monica Pier.

“Despite growing resistance from local communities, California’s state highway agency began purchasing right-of-way land, including expensive beachside parcels in Malibu, in the 1960s. The proposed freeway remained on planners’ maps until 1972, when it succumbed to bitter opposition among residents, civic leaders and environmental activists.”

The Santa Monica proposal is explained in a four-part story in the Santa Monica Outlook about the causeway (“Dreaming Big”).

Local businessman John Drescher, who had graduated from the University of Colorado in 1932 as an electrical engineer and moved to Santa Monica in 1938 to work as a pilot and a design engineer for aircraft components, came up with the plan.

Local businessman John Drescher, who had graduated from the University of Colorado in 1932 as an electrical engineer and moved to Santa Monica in 1938 to work as a pilot and a design engineer for aircraft components, came up with the plan.

In 1961, along with the company Seaway Enterprises, Drescher proposed the construction of an island causeway off the coast. (Alternative PCH Highway)

Located 4,000 feet from shore, the 30,000-ft.-long causeway would run parallel to the coastline from Santa Monica beach all the way north to Malibu. In the middle of this artificial archipelago would stretch a 200-foot wide freeway called “Sunset Seaway.”

Drescher claimed that the new highway would alleviate traffic on PCH and provide an additional 2.5 million square feet of public beach facing the ocean.

In addition to the new land, the area of water between the natural shoreline and the artificial causeway would become a series of marinas accommodating 1,700 small craft.

“The [Santa Monica City Council] for a time had a causeway committee that met in council chambers and discussed and debated the whole causeway question,” recalls Santa Monica businessman John Bohn, who was a member of the council at the time.

“The idea was a hit with the council and commission alike. Very soon the image of the causeway started cropping up in other places. An old poster for Douglas Aircraft shows a new airplane design flying high above Santa Monica and in the background, like some ghostly image of Atlantis, sits the causeway.

“There was support for the causeway from people well outside Santa Monica,” said City Council member Jim Reidy, a member of the Junior Chamber of Commerce at the time. “It was the Santa Monica dream.”

Then the tide turned and in 1964, the Santa Monica Civic Canyon Association entered the fray by “recruiting Hollywood star Jim Arness, already famous for his role as Marshal Matt Dillon in the TV series ‘Gunsmoke’, to appear in a short film entitled ‘Save Our Beaches,’ financed and produced by the SMCCA.”

In Part Four of the Outlook story (“The Dream Sinks”), the writer quotes former commission member Jim Mount: “Actually what had happened was the City Council and the county of Los Angeles had agreed on a three part participation and the city of L.A. was to be the third party. And then Marvin got elected as a councilman for this area and pretty successfully sank the whole thing.”

The article continues, “Councilman Marvin Braude was first elected to the Los Angeles City Council in 1965 and his timing was impeccable. Braude was a lifelong conservationist, an ardent bicyclist and co-founder and president of the Santa Monica Mountains Regional Park Association.

“Braude did not like what he was hearing concerning this outlandish scheme to relocate part of his beloved mountains to the Pacific Ocean. The environmentalists now had their man on the inside, and the playing field was leveled.

“’Marvin Braude scared them with the environmental damage it would do,’ says Mount of the new stance being taken in Downtown L.A.

“This was the seed of doubt that now took hold of people’s minds and would prove to be the death knell for the causeway project.”

In September 1965, Governor Edmund “Pat” Brown vetoed the causeway bill.

It’s now 2020, and residents want relief on a thoroughfare that was choked decades ago and is still a problem.

According to Tim Fremaux, other than signage and bollards, there don’t seem to be many alternatives.

Great update (and history!). Let’s hope this is followed through soon. It’s hard to believe that the simple, low-cost/no cost solution of cutting back those plants that block the specific half of turn lane sign (on Channel Road) to help hasn’t been done yet. That’d help toward the bigger picture of smoother traffic flow.