As of March 17, at 11:05 a.m., Thomas Waerner was still in first place after reaching the White Mountain checkpoint (953 miles from Anchorage). In second was Mitch Seavey, 60, who also reached White Mountain and moved up from fourth place yesterday. His dad ran the Idtarod in 1973, which inspired him to try it. After 11 Iditarods, he won the race in 2004. He also won in 2013 and 2017.

After White Mountain the next check point is Safety (55 miles) and then on to the finish line in Nome (22 miles).

Third is Brent Sass, fourth is Jessie Royer and in fifth is Aaron Burmeister. There are now only 48 mushers and teams left in the race. Out yesterday were Aaron Peck and Tichie Diehl, who scratched at Kaltag, and Larry Daughterty, who went out at Nulato.

There are winter storms in the forecast, one later today (Tuesday) and another predicted for tomorrow.

An Epidemic in Alaska in 1925 and the Heroic Effort by Men and Their Sled Dogs to Deliver the Vital Serum

Diphtheria was known as the “strangling angel of children,” because it caused the throat to become blocked with a thick, leathery coating that made breathing difficult. Without the antitoxin or vaccination, death by suffocation was likely.

The disease used to wipe out entire communities a century ago. In 1921, there were 206,000 cases of diphtheria, resulting in 15,520 deaths.

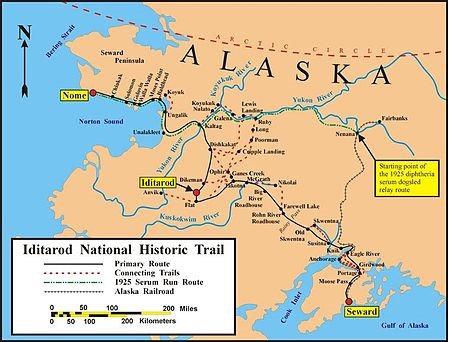

In January 1925, Dr. Curtis Welch diagnosed a diphtheria outbreak in Nome, Alaska. Knowing that the disease could kill the region’s population of 10,000 people, he sent telegraph messages to Fairbanks, Anchorage, Seward and Juneau asking for help.

“An epidemic of diphtheria is almost inevitable here STOP I am in urgent need of one million units of diphtheria antitoxin STOP Mail is only form of transportation STOP I have made application to Commissioner of Health of the Territories for antitoxin already STOP there are about 3,000 white natives in the district STOP.”

Of the Alaskan cities, a limited amount of serum was found in Anchorage.

Then it got worse for the sick kids because the only two planes available were in Fairbanks and had been dismantled and stored for the winter. A pair of pilots offered to fly the World War I vintage Standard J-1 bi-planes with open cockpits and water-cooled engines, but weather was iffy and plane crashes frequent.

The limited available daylight at this time of year prevented much flying. The temperatures across the Alaskan interior were reaching -50 degrees Fahrenheit. Governor Scott C. Bone had to decide between planes and dog teams. He went with the dogs.

His decision upset William Fentress (“Wrong Font”) Thompson, the publisher of the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner and an aircraft advocate, who then wrote scathing editorials about the decision and the relay.

Gov. Bone ordered additional antitoxin from Seattle. It was decided the available serum would be transported by train to the Tanana and Yukon Rivers about half-way to Nome. Then mushers and their dogs would take it the rest of the way.

The parcel left Anchorage by train on Monday, January 26, and at 11 p.m. on Tuesday the train reached the halfway mark, where the parcel was turned over to William (“Wild Bill”) Shannon, the first of the 20 mushers.

The parcel left Anchorage by train on Monday, January 26, and at 11 p.m. on Tuesday the train reached the halfway mark, where the parcel was turned over to William (“Wild Bill”) Shannon, the first of the 20 mushers.

He left immediately with his team of nine dogs, led by Blackie. On January 28, Shannon arrived at Tolovana at 11 a.m. According to reports, he and his team were in bad shape.

Edgar Kalland picked up the serum from Shannon and headed into the forest. The temperature had dropped to -56 degrees. The owner of the roadhouse at Manley Hot Springs had to pour water over Kalland’s hands to get them off the sled’s handlebar when he arrived.

George Nollner delivered to Charlie Evans at Bishop Mountain on January 30 at 3 a.m. Evans passed through ice fog where the Koyukuk River had broken through but forgot to protect the groins of his two short-haired mixed-breed lead dogs with rabbit skins. The two dogs collapsed with frost bite and Evans had to pull the sled himself. He arrived at the next site at 10 a.m.

Weather conditions continued to deteriorate for the next three mushers in the relay, Jack Nicolai, Victor Anagick and Myles Gonangan.

Gonangan reported white-out conditions and gale- force winds, which drove the wind chill to -70 degrees, before he transferred the serum to Henry Ivanoff at Shaktoolik.

On January 30, the number of cases in Nome had reached 27 and the antitoxin supply on hand was depleted. According to a reporter living in Nome, “All hope is in the dogs and their heroic drivers.”

Newspapers across the United States followed this heroic attempt at saving lives, calling it “The Great Race of Mercy.”

That day, a plan to fly serum from Fairbanks was supported by several U.S. cabinet departments and Artic explorer Roald Amundsen, but the plan was rejected by experienced pilots, the Navy and Governor Bone. Thompson’s editorials skewered Bone.

Meanwhile on the trail, Loenhard Seppala, who was a renown musher and his dog sled team with lead dog Togo had traveled 91 miles from Nome to meet Ivanoff at Shaktoolik to take the serum. When Seppala had not arrived, Ivanoff started on the journey with the serum.

The two met when Ivanoff got tangled up with a reindeer just outside Shaktoolik. Seppala took the serum, turned around and headed back towards Nome, crossing the exposed open ice of the Norton Sound to reach Ungalik after dark.

After a short rest for his pack, Seppala and his dogs left at 2 a.m., running across the ice, following the shoreline. They crossed Little McKinely Mountain, climbing 5,000 feet, before descending to Golovin, where Seppala passed the serum to Charlie Olsen on February 1.

Olson was blown off the trail and suffered severe frostbite while trying to cover his dogs with blankets. A blizzard was raging with 80 mph winds. He finally arrived at Bluff on February 1 at 7 p.m.

The next musher, Gunnar Kaasen, waited a few hours, hoping storm conditions would improve, but instead the wind and snow intensified. He took off into a headwind because he was concerned that drifts would soon block the trail.

Kaasen’s dog Balto led the team through visibility so bad that the musher said he could not see the dogs harnessed closest to the sled.

Somehow, he reached Point Safety ahead of schedule on February 2, at 3 a.m. The other driver was sleeping, unaware that Kaasen had pushed on. Kaasen reasoned it would take time for the new driver to prepare his team, so he decided to run the remaining 25 miles to Nome. He arrived at 5:30 a.m.

All told, about 675 miles were covered in 127 hours, in extreme sub-zero temperatures in blizzard conditions and hurricane-force winds. A number of dogs died during the trip.

It was still not clear if this medicine would be enough to stem the epidemic, so the U.S. Navy moved a minesweeper north from Seattle and the Signal Corps was ordered to light fires to guide the plane.

The serum batch from Seattle arrived on February 7 at Fairbanks. Acceding to pressure, Governor Bone authorized half of this shipment to be delivered by plane.

On February 8, the first half of the second shipment began its trip by dog sled, while the plane failed to start when a broken radiator shutter caused the engine to overheat. The plane failed the next day as well.

The second relay included many of the same drivers and dogs, under the same harsh conditions. The serum arrived on February 15.

Officially, seven deaths were attributed to diphtheria, but Dr. Welch estimated that upwards of 100 additional cases were in the Eskimo camps outside the city. (The “Spanish Flu” had hit the area in 1918 and 1919 and wiped out 50 percent of the native population of Nome.)

The mushers received letters of commendation from President Calvin Coolidge and a statue of Balto by sculptor Frederick Roth was later unveiled in New York City’s Central Park.

This incident helped spur the Kelly Act, which allowed private aviation companies to bid on mail delivery contracts. Within a decade, air-mail routes were established in Alaska. The last mail delivery by private dog sled under contract took place in 1938. The last United States Post Office dog sled route closed in 1963.