By LAUREL BUSBY

Special to CTN

Several friends of New Yorker Tom Falzone have died from Covid-19.

He knows cadets at West Point, where he coaches the parachute team, who have lost grandparents.

Back in May, the 1979 PaliHi graduate told Circling the News, “You see whole storage trucks for dead bodies in Central Park; it’s unbelievable here. It’s the epicenter…. It hits a little bit closer to home compared to most states.”

Falzone lives north of the city in the Shawangunk Mountains.

While no other state has witnessed the flood of deaths that New York has experienced—24,348 as of Monday this week—all have witnessed changes wrought by the pandemic.

For Falzone, those changes began in mid-March while he was training his skydiving team at Fort Bragg in North Carolina over spring break. He was asked to stop the training, not return to the campus in N.Y., and instead send each cadet back home.

He also came home to the small mountain house he shares with his girlfriend, Christine Kelley. They have no neighbors and shop for groceries at a farmers’ market, so in many ways, it’s been an ideal place to be sequestered.

“I am very fortunate. I still have a job. I still have a paycheck,” Falzone said in May. But in New York City, “it is chaos right now. A lot of my friends have abandoned Manhattan and run up here. They’ve asked, ‘Can we move in with you?’ Absolutely not. I live in a tiny house. There’s no room.”

Falzone still coaches his team, although that coaching now consists of Zoom meetings instead of the active physical adventures it used to entail. In addition, Falzone, who annually returns to Southern California for the skydive that leads off the Pacific Palisades Fourth of July parade, will not be flying here for the cancelled jump.

Instead, he is tackling projects at home. Some connect to a successful home business he shares with Kelley called Liquid Altitude. The company sells bottled sangria, although sales have decreased dramatically due to the coronavirus. Most of their sales stem from trade shows and tastings at liquor stores. Forty shows have canceled, and the tastings had to stop. The couple also had planned to test and roll out a carbonated, canned drink called White Mule—white sangria mixed with ginger beer. This release had to be canceled.

“We’ve been hit hard, but I have no complaints,” Falzone, 60, noted. “This is a small sacrifice compared to what my friends are going through.”

The bigger personal loss for Falzone has been a temporary end to both skydiving and coaching. He misses the routine of driving to West Point and training his cadets, who have won the collegiate championship in skydiving for three of the past five years.

He has devoted most of his adult life to the sport, and, looking back, it’s funny to think how it all began with a chance occurrence. In 1986, at a barbecue with friends, he happened to catch a television special about parachutist Carl Boenisch on ABC’s Wide World of Sports. Falzone got so inspired that he convinced 30 people at the party to join him on a first skydive.

He promised to organize the whole thing. He found a drop zone and a company that could instruct them, and then chartered a bus to get everyone there on the appointed day, about six weeks after the party.

But soon, he started getting phone calls from his friends that they couldn’t make it after all.

“People were dropping off like flies,” Falzone said. “It was down to 25, then 20, then 15, then 10. I canceled the bus.” He kept calling the skydiving company to let them know of the reductions, which further withered to five and then one solitary friend willing to take the risk.

However, on the appointed day, his friend didn’t appear at Falzone’s house, so he drove to the skydiving company alone. When he arrived and introduced himself, the proprietor told his co-worker, “Hey Linda, it’s Mr. 30.” Then he added, “You’ve got some balls, kid, for still showing up.”

Falzone understood his friends’ reluctance to jump out of an airplane, but for him, the decision to jump that day was perhaps the most impactful decision of his life.

“Everyone is intimidated; it’s daunting,” he noted, but for him, that first jump began a lifelong love of skydiving. “It just took my breath away.”

Every weekend after that, he was skydiving. He made more than 500 jumps over the next two years. The interest also set in motion a new career that he would never have predicted.

Every weekend after that, he was skydiving. He made more than 500 jumps over the next two years. The interest also set in motion a new career that he would never have predicted.

Before then, Falzone had worked his way through Cal State Northridge by flipping houses. He would buy a fixer-upper, add a bathroom or remodel a kitchen, and then sell the home. After graduating, he grew tired of always living in a construction zone, and he was looking for a new career. His family urged him to enroll in law school, and he was open to the idea.

However, by then, he had developed enough skill at skydiving to be invited to participate in a world record effort—a 144-way, which is a skydive of 144-interconnected parachutists. At the time, this would be the largest number of skydivers who would fall together in formation in history.

The trip would mean he would be a week late for the start of law school, but he thought it was worth it.

The jump was “successful; we held the formation for 8.8 seconds on August 8, 1988,” Falzone recalled. “I got back home, and I said, ‘Yeah, I don’t want to be a lawyer.’”

However, he did want to spend more time skydiving, so he focused on finding a way to increase his participation in the expensive sport. The main avenues were coaching and competing, and he decided to do both.

In the 1990s, Falzone won numerous medals at the U.S Nationals, as part of various teams creating 10- or 16-way formations. During those years, he garnered so many medals that he no longer remembers how many he won. He estimated about 20 golds and a dozen or so each of silver and bronze.

His success in competition helped him earn coaching jobs, which eventually led to the job offer at West Point. He first worked part-time for the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, before being offered the full-time position in 2009.

“I could never have dreamt of something like that,” Falzone said. “It’s really been an honor.”

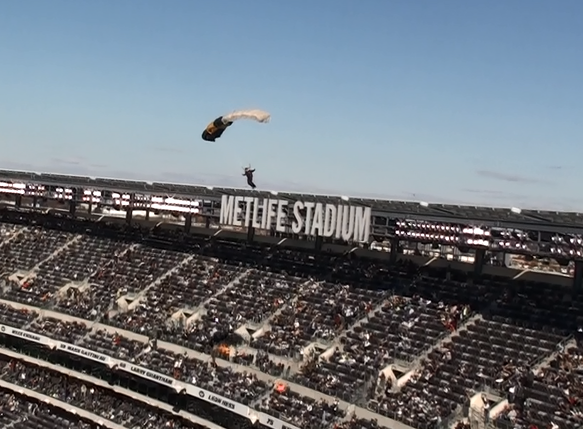

As a leader of this group of 30 to 40 male and female cadets, Falzone works to develop exacting skills so they can safely jump into multiple venues, including MetLife Stadium, Citi Field, and Yankee Stadium. Through their four years together, he also works to teach corollary skills that will not only help them safely return to Earth but will also benefit them as they venture into their military careers.

“It’s about teaching them leadership and teaching them to dot their i’s and cross their t’s,” Falzone said. “You only get one shot to land. It’s a really challenging thing to do. Even at 34 years in the sport, I have a high respect for what we do. To share that with cadets, it’s really a privilege.”