Mountain lion P-30 was found dead by National Park Service biologists on September 9, 2019.

Photo: NPS

By MARISSA PIANKO

Circling the News Writer

Early this fall, biologists from the National Park Service trekked deep into Topanga State Park in search of a mountain lion, called P-30. His radio collar had sent out a mortality signal, so they feared the worst. Upon reaching the site, they discovered the dead body of the 6-year-old male, with no obvious signs of injury.

The biologists systematically collected P-30’s remains and brought him in for a necropsy. Scientists soon discovered that he had massive internal bleeding and brain hemorrhaging. The cause of death was determined to be anticoagulant rodenticide, otherwise known as rat poisoning.

This is not an isolated incident. Evidence has shown that anticoagulant rodenticide, the most common poison used for rodent control, is having a detrimental effect on the local wildlife population.

In a 15-year-long study published by the National Park Service (NPS), researchers in Southern California have documented the presence of anticoagulant rodenticide compounds in 23 out of 24 local mountain lions that they have tested, including a three-month-old kitten.

The NPS published an article by Dr. Seth Riley, an ecologist and the wildlife branch chief for Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area (SMMNRA), who wrote, “Just about every mountain lion we’ve tested throughout our study has had exposure to these poisons, generally multiple compounds and often at high levels.”

And it’s not just mountain lions that are affected. “A wide range of predators can be exposed to these toxicants – everything from hawks and owls to bobcats, coyotes, foxes and mountain lions. Even if they don’t die directly from the anticoagulant effects, our research has shown that bobcats, for example, are suffering significant immune system impacts,” Dr. Riley said.

Anticoagulant rodenticide works by blocking an animal’s blood-clotting factors, causing them to bleed out uncontrollably. It is a slow and painful death, according to California Wildlife Center Veterinarian, Stephany Lewis. Victims of anticoagulant rodenticide typically have similar symptoms. Dr. Lewis states that, “Commonly, they are bleeding out of a small wound, subcutaneously or bleeding into their lungs or body cavity. I’ve seen them bleed out of their eyes and into their brains.”

Last year, the California Wildlife Center documented 10-15 cases of anticoagulant rodenticide poisoning. However, Dr. Lewis says that number is under representative of the actual cases.

Rodenticide poisoning can only be clinically determined after an animal’s death, meaning that those who survive are never identified. Further, she believes there are far more cases that they don’t see.

“I really suspect that we are not seeing nearly as many as there are out there because it’s a slow process. It’s a slow death for them. And most of those sick animals are going to go hide.”

A vast majority of predators are poisoned secondarily, meaning they are eating a small animal that has directly consumed rat poisoning. These are typically the cases that Dr. Lewis sees at California Wildlife Center.

As she ponders her most recent patient suffering from rodenticide poisoning, she looks down and sighs. “It was a beautiful adult female red-tailed hawk. She was in good body condition and had no major injuries. She just had a very small wound on her chest that was bleeding excessively. Compared to the size of the wound, there was just blood all over her feathers and she was severely, severely anemic. Her mucous membranes were totally white, and all of her vessels totally collapsed. Her blood pressure was very low. She was so weak that she couldn’t stand or barely open her eyes. That’s typically how they present to us. They aren’t going to present to us in the early stages because they would be able to fly away. By the time they come to us, it’s really, really late. Unfortunately, she passed away within an hour of getting here.”

Red-tailed hawk ingested rodents that had eaten rodenticides. She died from the poison.

Photo: Stephany Lewis California Wildlife Center

There are two categories of anticoagulant rodenticide, which are typically used in bait boxes. First generation anticoagulant rodenticide, developed in the 1940s, has a short half-life, meaning the poison doesn’t last long in the body.

Second generation anticoagulant rodenticide (SGARs) came out in the 1970s, in response to rodents developing a resistance to first-generation poisons. It is much stronger than the first generation and remains in the body for a longer period of time. The poison accumulates in the liver, delivering many times the lethal dose to a rodent. Studies have shown that SGARs are typically responsible for predator deaths in cases of rodenticide poisoning.

The irony is that anticoagulant rodenticides are not effectively controlling the rat population. Without the presence of rodenticides, healthy natural predators, like hawks, coyotes and bobcats, consistently hunt rodents, effectively reducing the rodent population. Instead, those natural predators are being poisoned. And according to the group Poison Free Malibu, which advocates for pesticide regulation, there are many effective and safe alternatives to anticoagulant rodenticides.

Along with Poison Free Malibu, there are government, environmental groups and concerned citizens that have recognized the detrimental impacts of anticoagulant rodenticide on local wildlife.

After comprehensive studies, in 2008, the EPA banned SGARs for consumer use, while still allowing professional exterminators to utilize them. However, three major rodenticide manufacturers sued the federal government to prevent this action, delaying removal of these rodenticides from shelves for years.

In the meantime, several advocacy groups in California, including Raptors are the Solution (RATS) and Poison Free Malibu, worked tirelessly to ban consumer use of SGARs on a State level. Ultimately, their efforts paid off and, in 2014, the California Department of Pesticide Regulation (DPR) banned the use of SGARs for consumer use.

However, in the four years following this ban, the DPR, in conjunction with California Fish and Wildlife, continued to monitor exposure rates of SGARs in wildlife, and remarkably, they were not decreasing. Kian and Joel Schulman, co-founders of Poison Free Malibu, point to exterminators, who are the primary users of SGARs. The SGAR ban, they say, must be extended to commercial use.

Since California state law, which is limited to consumer use, has been ineffective in decreasing exposure to SGARs, the Schulmans are working to modify local laws to prohibit the use of SGARs universally.

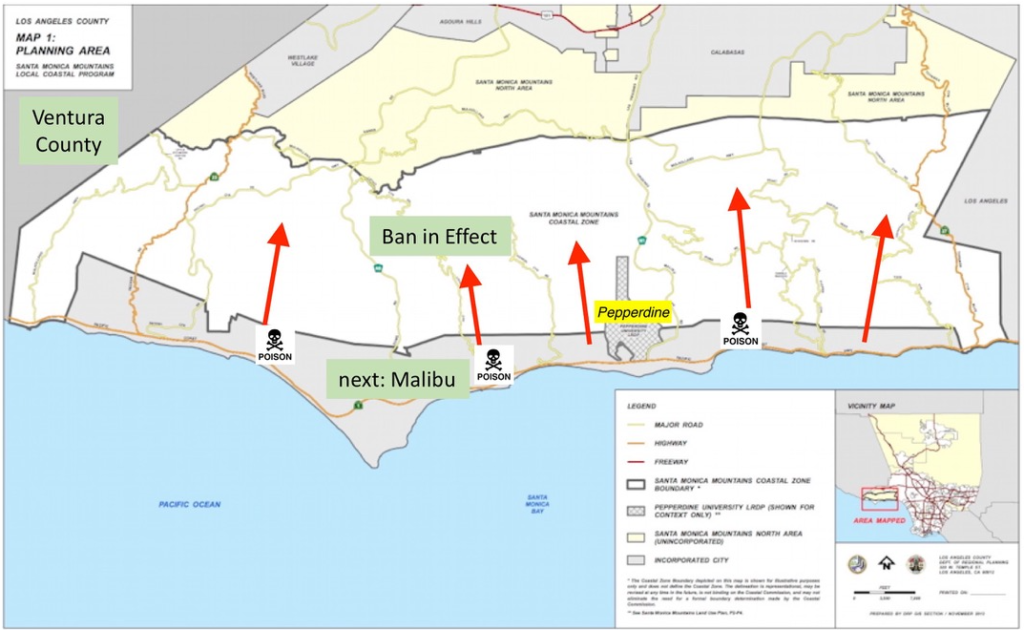

In October 2014, they worked to incorporate an amendment into the Local Coastal Program of the California Coastal Commission which successfully banned ALL use of SGARs in the unincorporated Santa Monica Mountains Coastal Zone Boundary [shown as white area on map below].

However, the city of Malibu is not included in that ban [shown as grey area along the coast on map below]. As a result, the Schulmans worked with the Malibu City Council to extend the ban to the city of Malibu. But they have come up against some resistance, which has delayed the ban.

According to a November 19 email from Poison Free Malibu, “The Malibu City Council unanimously voted in favor of doing it in Malibu too SEVERAL TIMES, but the City Attorney, Christi Hogin, opposed and has blocked it, claiming that the Coastal Commission does not have this well- established power, and has stalled it for five years.” Christi Hogan did not reply to a request for comment.

The Schulmans are pushing forward in their efforts to ban SGARs. On December 9, Poison Free Malibu will again present at the Malibu City Council meeting, requesting a local ban on rat poisons and other toxic pesticides in Malibu.

Their hope is that residents will attend the meeting and speak out in support of the ban. City Attorney Christi Hogan has written a memorandum in anticipation of this meeting, expressing the illegality of pursuing a local ban on rodenticides, while still acknowledging “the alarming and disgusting effects of these poisons.” She cites State Preemption Law, which dictates that city laws cannot contradict or supercede state laws.

In the meantime, an updated state law is in the works. Assemblymember Richard Bloom [D-Santa Monica], whose district covers a vast majority of the Santa Monica Mountains, introduced Assembly Bill 1788 to the State Senate in hopes of creating stricter regulations on anticoagulant rodenticides.

According to his website, “AB 1788 seeks to take stronger measures to protect children, pets, and wildlife from unintentional rodenticide poisoning by banning the use and sale of second-generation anticoagulant rodenticides statewide and banning the use of first generation anticoagulant rodenticides on state lands and buildings.”

Assemblymember Bloom’s Senior Field Representative, Tim Pershing, says the bill has been held back until next session, which commences in January 2020. The biggest issue around the bill, according to Pershing, is figuring out how to implement and enforce it. He is confident they will have a resolution, though.

Hundreds of studies have been done on the impacts of anticoagulant rodenticide and the consensus is that the effects on wildlife are merciless and dramatic. Dr. Seth Riley issues a startling warning in his study on mountain lions: “High levels of exposure in free-roaming small mammals in conjunction with widespread carnivore exposure indicates that current rodent control activities (whether legal or off-label use) are putting all predatory species at risk.”

The question is, will the proposed local or state regulations pass and, ultimately, help to mitigate this alarming risk?

We know this is a serious problem. On the Village Green and in our own yard we use the black boxes that have traps in them, not poison. People might want to look into this method of control.