By TIM CAMPBELL

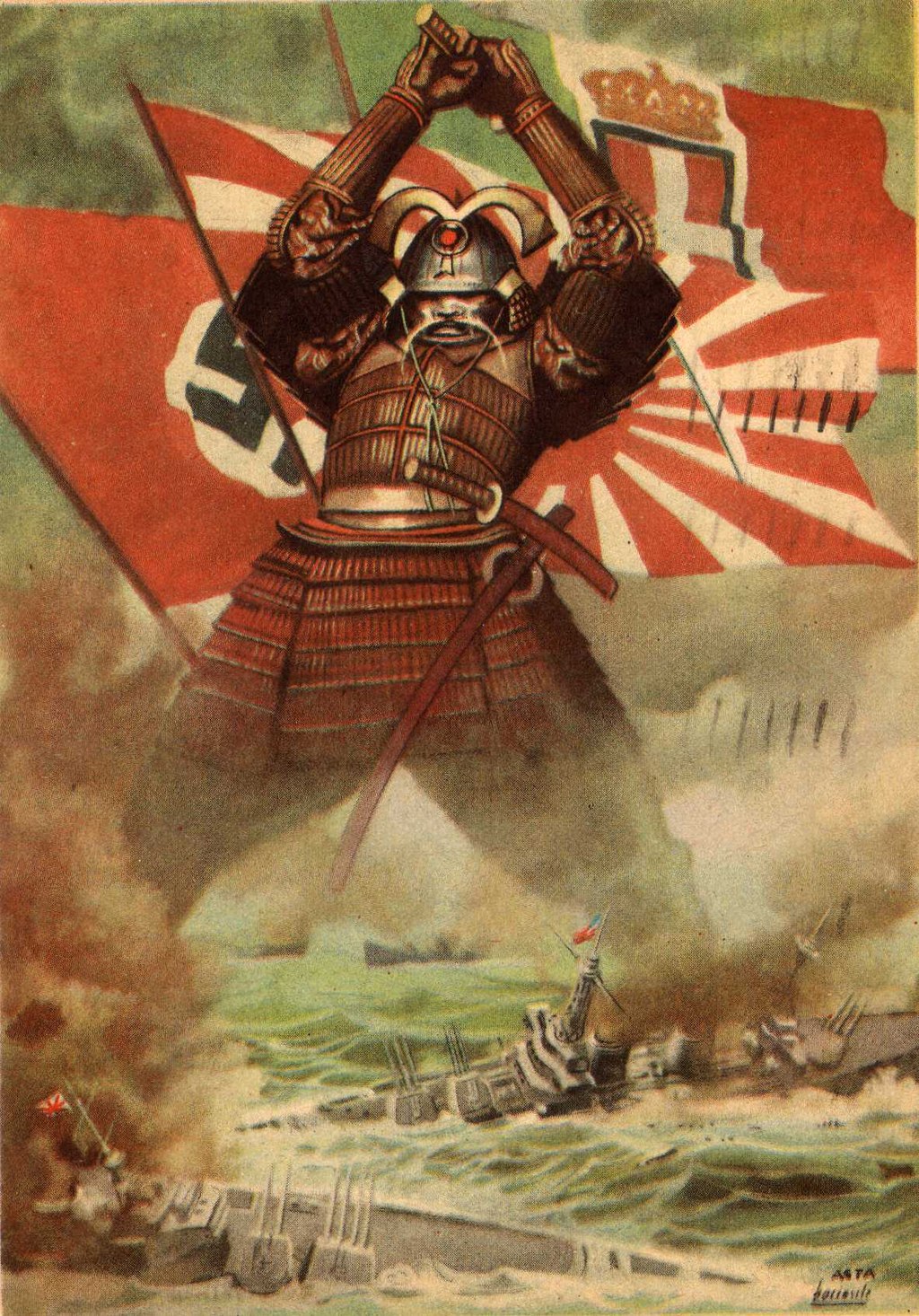

In the summer of 1945, once the US knew the atomic bomb worked, the western Allies issued an ultimatum to Japan: surrender or face complete destruction. The Japanese government met each call to surrender with what is known as Mokusatsu, or “to treat with silent contempt.”

Although revisionist historians suggested the Allies misinterpreted the word and it was supposed to mean “ignore,” modern researchers agree with the Allies’ 1945 understanding. War hawks in the Japanese government hoped that by not responding to the surrender demands, they would eventually wear down the allies and make them accept peace on Japan’s terms. It didn’t work.

When it comes to negative news about homelessness, Los Angeles’ elected leaders seem to be following the same path of silent contempt. They habitually try to ignore anything that diverges from their false narrative of success. Just a few examples include:

- When Jaime Paige and Christopher LeGras exposed the fact that almost half of the motel rooms purchased under Project Homekey have been vacant for as long as two years. City officials said nothing to show they were interested in addressing the problem.

- When Paige and LeGras found more than 70 percent of the rooms purchased by the County were vacant, the Board of Supervisors did not respond, other than to send a few generic emails about construction costs and regulatory issues.

- When Sue Pascoe of Circling the News revealed LAHSA’S failure to count homeless in beach areas, officials responded with a vacuous word salad that didn’t address the count failure.

- When the L.A. Alliance for Human Rights released a report showing the County has chronically underspent funding for mental health and other support services for the unhoused, County officials’ response was it “didn’t tell the whole story”, but offered no data to refute the report’s findings. Since the report used county financial and program data, not telling the whole story would mean the county did not provide accurate budget or performance documents. The response was very similar to a 2020 State Auditor report that showed the county chronically underspends its Mental Health Services Act money, to the point it is sitting on an unencumbered balance equal to 175% of its operating budget. The County claimed the audit’s numbers were inaccurate, but never offered a verifiable alternative amount.

- At an October 2 hearing in federal court, independent auditors described how the city, county, and LAHSA were stalling or refusing to provide data required to measure homeless program performance. Officials responded with vague assurances the data would be forthcoming—if it exists.

- When the City Controller announced he was investigating nonprofit organization Urban Alchemy after a video of one of its employees using a perssuer washer to force a homeless person off a sidewalk, L.A.’s City Council continued to grant the nonprofit large service contracts. A few months after the Controller announced the investigation, the City Council and City Attorney inexplicably tried to shut it down.

- When Christopher LeGras exposed serious problems with LAHSA’s latest PIT count, officials continued to insist the count was accurate and that it showed a meaningful decrease in homelessness.

These are just a few examples of how local officials try to ignore or dismiss criticism of their programs. Often, there’s more contempt than silence.

I’ve read official reports blaming “NIMBY’s” for the city’s failure to require its providers to properly manage shelters, and for the county’s inability to create more mental health beds. When public agencies choose not to hurl insults themselves, they can depend on their surrogates in the advocacy industry, who are quick to brand negative news as “hating the homeless” and pack Council meetings with their screaming followers.

Seventy-nine years ago, the Japanese government used silent contempt and obfuscation on its own population as well as its enemies. The government withheld news of military defeats from the population, even as American bombers appeared in the skies above their cities.

Our local government uses the same practice. I defy anyone to point out a single instance where an elected official has stood up in front of the press and admitted homelessness programs have a performance crisis. Even as independent auditors detail the lack of performance measures and payments made without documentation, officials remain silent or defend their agencies.

What are we making of our elected leaders’ silent contempt? They treat their constituents as obstacles to be overcome instead of the people to whom they are responsible.

When residents raise legitimate concerns about homelessness program performance, they are subjected to lectures about our “unhoused neighbors”, or promised success is just around the corner (as long as taxpayers continue to cough up sufficient revenue).

Our leaders’ attitude also shows tremendous arrogance. Despite multiple press stories exposing systemic failures in homelessness programs, despite professional auditors questioning how public money is being spent, despite the city’s own Controller investigating at least two nonprofits, despite one of Judge Carter’s special masters suggesting there are signs of fraud in the audit’s evidence, and despite all these problems, public officials continue to insist their programs are working and are the only solutions to homelessness.

Just as the arrogance of Japan’s leaders brought their country to the edge of annihilation, so local leaders turned a blind eye to the suffering on our streets.

They are more interested in political posturing, defending theories about social justice, and guaranteeing the free flow of revenue than in solving homelessness. One of the most poignant examples of our leader’s arrogance is a recent L.A Times story about the nonstop calls at an LAFD station near MacArthur Park.

Between January and August 2024, medical calls related to drug overdoses outnumbered fire calls by almost 17 times (599 to 36). As columnist Steve Lopez wrote, “All of this is the normalized reality of a neighborhood that once stood as a gem of the city, and now suffers in wait for someone, anyone, to stand up and say this should not exist, cannot exist, and must end, for the sake of civility and for the benefit of the working people who make up the majority of the residents here, raising children who deserve better”.

The neighborhood around MacArthur Park is in Councilmember Eunisses Hernandez’s district; she is one of the most vocal defenders of Housing First and social justice on the Council.

While she pontificates about “criminalizing homelessness,” paramedics are constantly responding to overdose calls, sometimes for the same person multiple times a day. The Times story says she created an overdose response unit for the park. Note this is an overdose response unit, not an overdose prevention unit, consistent with Harm Reduction policies.

We know from community advocacy groups like the Santa Monica Coalition that the way the County Department of Public Health practices Harm Reduction – it is 100 percent reactive; it responds to overdoses after the fact, and actually makes them more likely by distributing drug paraphernalia while offering no diversion services. Councilmember Hernandez often frames homelessness in terms of race and economics. Yet, she seems fine, perpetuating a system that kills more people of color and the poor at far higher rates than other populations.

Our leaders’ practice of silent contempt reveals an absolute disdain for nearly everyone in the community: housed residents and taxpayers who expect results for the billions spent on homelessness; business owners who deal with the effects of the mentally ill and substance abusers who regularly drive customers away; unhoused people, more than 70 percent of whom are unsheltered and in desperate need of adequate shelter and services; and even their own employees, like the paramedics who live with the stress of responding to endless overdose calls and the deaths that accompany them.

It seems the only group many leaders are interested in is the one that finances their campaigns and who agrees with their willingness to experiment with the livelihood and lives of the people they should serve.

Hi, Sue! The most haunting FACT I have read and heard about and seen with the unsheltered is that they don’t WANT to be sheltered. Too confining. Supervision. Rules. And not as nice as where they’re living now (little joke…sort of). What do you do when someone is offered an empty motel room or apartment and they say “NOPE”? We can’t force them to be housed and safe and treated without their consent, remember?? It’s a real law firmly on the books for a long time. And no public servant will ever take the risk of leading the charge to take it off the books. ACLU battling Reagan – and losing – blew up all the options for us “ordinary, decent citizens” to find any way out of the filth and menace steadily growing around us.

Well said! It seems that accountability is lacking at all levels of our government. They keep putting out their hands for ever larger bond issues when there is still unspent money from a previous bond for the same purpose and with no accounting of the expenditures that have been made. I was talking with a friend today about this very thing and the upcoming election, and she suggested that each level of government needs a CFO to manage and account for the money.