By REECE PASCOE

If you have ever driven up to Lake Tahoe, you have seen Mono Lake.

It is on the eastern side of Highway 395, a few hours south of Tahoe. I took that drive back in 2010.

When I saw Mono Lake, my first impression was that it was a dry lakebed.

Mono Lake has been in the news recently because of the low levels of the lake, and the continued diversion of water by the Los Angeles Department of Power and Water (DWP).

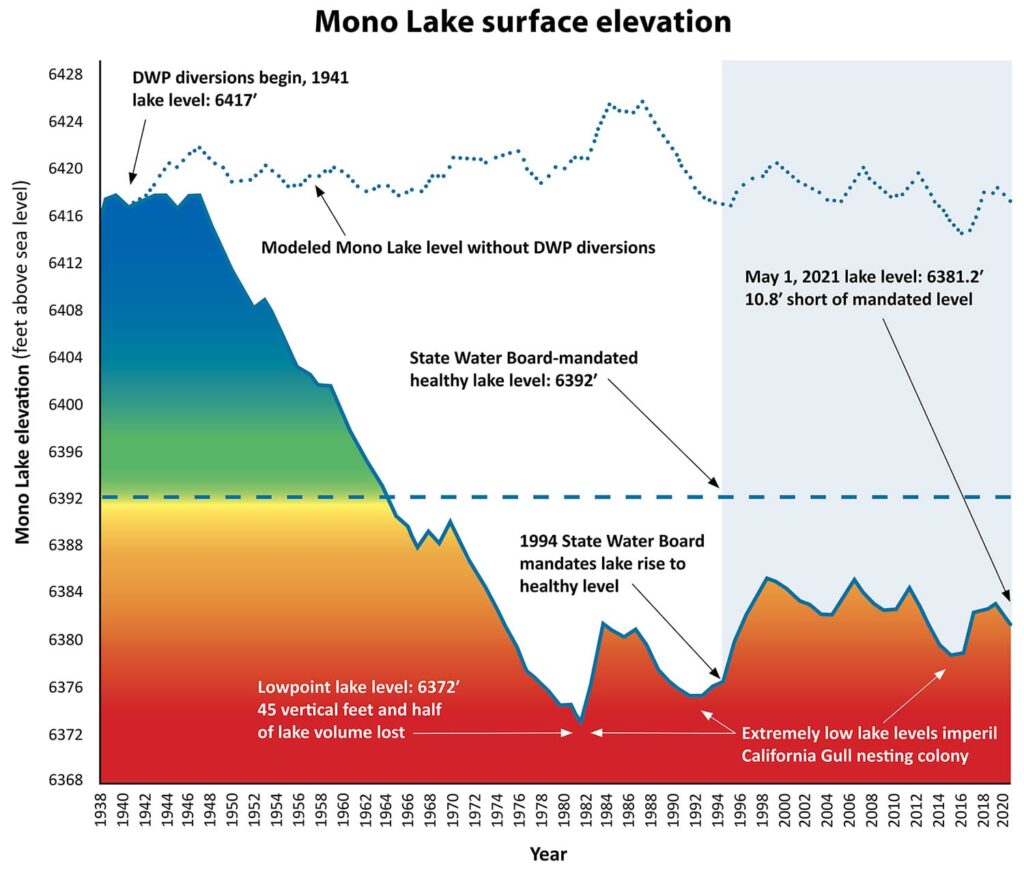

In 1940, the city of Los Angeles gave its rights to DWP to divert water from tributaries of Mono Lake for municipal and hydroelectric use. At the time there was anticipated ecological damage, but water was still allowed to be diverted from the lake.

From 1941 to 1982, Mono Lake saw a drop of 45 ft. in water level, to a low of 6,372 ft. above sea level. Due to unique shape of the 70-square-mile lake, it has also seen a reduction of 30 percent of surface area.

The Mono Lake committee has been working since 1978 to protect the lake and restore its tributary streams.

In 1979, the National Audubon Society and the Mono Lake Committee sued DWP arguing the water divisions to Los Angeles did not comply with the Public Trust doctrine.

The California Supreme Court helped clarify the legal framework of public trust surrounding the water rights granted to Los Angles, and agreed with those who filed the lawsuit.

“The principal values plaintiffs seek to protect… are recreational and ecological—the scenic views of the lake and its shore, the purity of the air and the use of the lake for nesting and feeding the birds. Under Mark v. Whitney it is clear that protection of these values is among the purposes of the public trust.”

This legal outcome led to many different accommodations that had to be met, which included fish/trout, air quality, the different types of plant life and the birds (this is a critical stopover site for millions of migratory shorebirds and water fowl).

The legal document specified each aspect that had to be met, which was tied to the forecasting outcomes of different water levels.

In 1984, the Committee, California Trout and the National Audubon Society sued DWP again to protect Mono Lake’s tributary streams. They were successful and water began flowing into dry channels, the first time since the 1940s.

The court had also allowed a water-depth transition period from a low level of 6,372 to a required 6,391 feet above sea level. Documents stated that “LADWP’s water right licenses should be amended to limit diversion in the following respects until the water level of Mono Lake reaches 6,391 ft.”

This level has never been reached and, in this transitionary period, there are also many limitations on water diversion. One of them is “No diversions until a lake level of 6,377 feet is reached: no diversion of water should be allowed under LADWP’s water right licenses any time that the water level in Mono Lake is below or is projected to be below 6,377 feet during the runoff year of April 1 through March 31.

The current Mono Lake level is at 6,379 feet.

Mono Lake is 2 ½ times saltier than ocean sea water. With water being diverted and evaporation, this is very troubling because it causes toxic dust storms. The higher salt content is a problem with local fauna and other wildlife.

A balance of water/salt and shore area is important because this is a breeding ground for more than 300 resident and migrant birds.

Another aspect of diverting water from the tributaries is the fisheries. The lower water flow and lower water level destroy places for spawning. (visit: https://www.monolake.org/learn/aboutmonolake).

(Author’s note: One solution to the Los Angeles water problem might be to revisit the Colorado River compact of 1922. This compact specifies not just for Los Angeles or California, but also for all Southwestern states. Water usage is based on agriculture, husbandry and population size. And every decade the percentage of usage gets updated on demographic shifts.)