(Editor’s note: Brookings, South Dakota, held a book festival at South Dakota State University at the Oscar Larson Performing Arts Center on September 24-26. The event was free and open to the public. In addition to numerous workshops, such as journal and poetry writing, and how to complete and have books published, there were several well-known authors in attendance, such as William Kent Krueger. Krueger, published by Simon & Schuster, is an American novelist and crime writer best known for the novels that feature Cork O’Connor. In 2005 and 2006, he received the Anthony Award for best novel. His stand-alone book “Ordinary Grace” won the Edgar Award for Best Novel of 2013.)

Author William Kent Krueger spoke about the art of writing.

“To be a writer is to live in hope,” William Kent Krueger told the about 100 people who had gathered Founder’s Recital Hall at 9 a.m. on a Saturday morning.

He told the audience, he uses his full name on his books, but “I’ve always gone by Kent.”

He is the author of 19 Cork O’ Connor books, the first being Iron Lake, and two stand-alone novels. He started with an opening line from Moby Dick because it was a journey of a young person and a vision of what is possible.

Krueger said we all go through life with the vision of “what’s possible,” but that some of us find it later in life and then explained how he became a published writer in his 40s.

His father was a high school English teacher, who walked around the house saying, “doesn’t anyone use a dictionary?”

Krueger’s first attempt at a storytelling was in third grade, when he wrote about a dictionary that had legs and could walk. He said he received high praise from the teacher and his father for the story. “In third grade, I knew I wanted to be a writer.”

His father had him read Ernest Hemmingway, and “At 18, I wanted to be Hemmingway.”

In an interview for Shots magazine, Krueger said about Hemmingway, “His prose is clean, his word choice is perfect, his cadence is precise and powerful. He wastes nothing. What’s not said is often the whole point of a story. I like that idea, leaving the heart off the page, so that the words, the prose itself, is the first thing to pierce you. Then the meaning comes.”

He attended Stanford in the 1970s, but during student protests got into an argument with the administration and did not complete his degree.

He kept writing, while digging ditches, logging timber and in construction.

“When I hit 40, I hit a mid-life crisis,” he said, and noted that he decided to write a book. He did research and discovered that everyone loved mysteries and “I decided to write a mystery.”

His father had not encouraged mysteries, because they were not considered great literature, so “I never even read even any Nancy Drew as a child.”

He started his mystery education by reading Tony Hillerman, who is known for his strong characters and tribal policeman who solve crime on the Navaho reservation.

“He created profound characters with a strong sense of background,” said Krueger, who explained that conflict is essential in any novel.

Krueger, who lived in Minnesota, was aware of the conflicts there that center around weather, the landscape and cultural differences.

He decided to make his main character half Anishinaabe (Ojibwe). “I started by reading everything I could get my hands on about the culture,” he said, noting that he also gives his novels, after they are finished, to Ojibwe friends, to make sure the traditions are correct.

His main character Cork O’Connor is half Ojibwe, half Irish American. Krueger said he chose the name Cork, because he wanted a character who, no matter what happened in life, was resilient, would always come back.

Krueger said that authors of series make a choice for protagonists to either make them static or dynamic.

An example of a static main character would be Sherlock Holmes, but this author elected to make Cork dynamic. Those that are fans of the series have followed Cork as he’s aged and watched his children become young adults.

The author said that the first dictum of writing is to “write what we know,” and he created a family man and the “saga of the Cork O’Connor clan.”

He finished his 500-page first novel Iron Lake and sent it to 30 publishers in New York. “I only got six xeroxed negative replies and some were not even centered on the paper,” he said.

He finished his 500-page first novel Iron Lake and sent it to 30 publishers in New York. “I only got six xeroxed negative replies and some were not even centered on the paper,” he said.

It was when friends told him he should try a Chicago agent Jane Jordan Brown, that his hope of becoming published shifted.

“I crafted a letter and sent it to her,” he said, “And she agreed to read the book.”

After reading it, she told Krueger if he could cut it by about 100 pages, she would reread it.

“I took a year and trimmed about 120 pages, and sent it back to her,” he said.

Brown sent his book to six publishers in New York and when Krueger received an offer from St. Martin’s Press for a first novel, he was ecstatic and asked, “Where do I sign?”

She didn’t let him because she was convinced there would be a counteroffer from Simon & Schuster, which she received. Once again, Krueger asked, “Where do I sign?”

Brown didn’t let him sign until she had counter offers from both and he ended up with a lucrative two-book deal from his current publisher.

He was asked which was his favorite novel. “Iron Lake, because it was my first. I like Thunder Bay because of the theme about the sacrifices we’re willing to make in the name of love,” Krueger said. Lightening Strike because it is about Cork as an adolescent and now my new book Fox Creek.

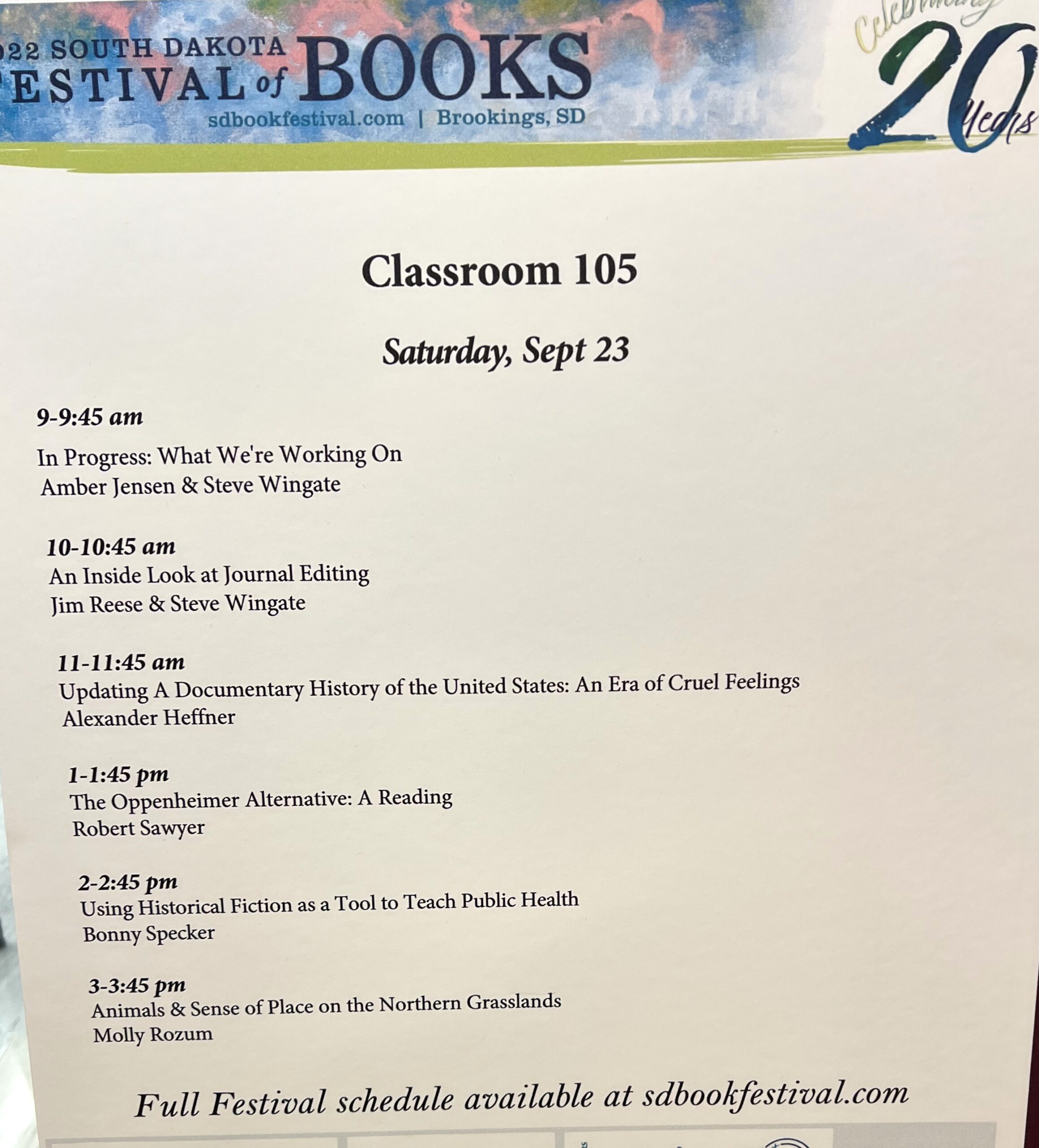

Friday and Saturday saw numerous writing events at several venues.