Ann Vileisis, an independent scholar and award-winning author of three books that explore culture and nature through history, will speak at the Pacific Palisades Historical Society annual meeting at 7 p.m. on Tuesday, May 23, at Pierson Playhouse, 941 Temescal Canyon Road.

The author’s illustrated lecture, “Abalone: The Remarkable History of an Iconic Shellfish,” is free, but people are asked to RSVP to pacpalhistoricalsociety@gmail.com to be assured of seating. This Lorraine Oshins Lecture is made possible with the support of the family of the former PPHS president.

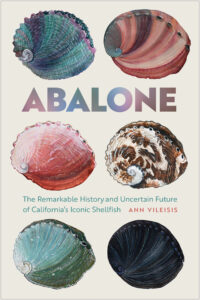

“Prized for iridescent shells and delectable meat, these unique shellfish inspired indigenous artisans, bohemian writers, California cuisine and the popular sport of skin diving, but also became a highly coveted commercial commodity,” Vileisis writes in Abalone: The Remarkable History and Uncertain Future of California’s Iconic Shellfish.

“Prized for iridescent shells and delectable meat, these unique shellfish inspired indigenous artisans, bohemian writers, California cuisine and the popular sport of skin diving, but also became a highly coveted commercial commodity,” Vileisis writes in Abalone: The Remarkable History and Uncertain Future of California’s Iconic Shellfish.

“There arose a persistent belief in abalone abundance, with fishermen and early fisher managers believing that continually taking millions of animals was sustainable, as long as size limits were followed,” she said in a Q & A about Abalone (visit: annvileisis.com).

Vileisis notes there that it is relevant to know the story of abalone because of the consequences of misperceiving history. “Studying history is important because the story we tell ourselves about how we got to where we are today is the stepping off point for the future.”

Not until sea otters rebounded in the 1950s and scientists came to understand El Niños as a recurring phenomenon did people begin to grasp the complex dynamics that affected abalone and other marine animals in kelp forest ecosystems.

Abalone are important to that ecosystem because the mollusks eat drift kelp–tiny bits of kelp that tear free.

Vileisis said that abalone “basically survive on what might be considered ‘crumbs’ of the kelp forest. They also hold space on the surface of reefs; when there are too few abalone, creatures like tubeworms or urchins can take over, making it impossible for the next generations of abalone to settle and thrive.

“I was surprised and somewhat dismayed to learn that citizens had tried, again and again—for over 100 years—to conserve California’s abalone,” Vileisis writes. “It was sobering to realize how difficult it is to recover an endangered species—even mollusks like abalone.”

She noted that the California Department of Fish and Games did not restrict abalone fishery until it was too late. “To me, the lesson is clear: we simply can’t wait until after animals decline to low levels to try to conserve them.”

CTN asked Vileisis in May 11 email why humans let creatures we cherish become so imperiled.

In a May 13 email to CTN she wrote “That was one of the key questions I wrestled with in my book research!

“Of course, abalone are animals that have been cherished for millennia–for seafood, for their beautiful shell material, and as kindred spirits. It turns out that the wild animals that we use as food tend to have it hardest because it’s so hard to control human appetites.

“Though we can aim to control overfishing, other larger environmental stressors pile on, too–such as marine heat waves and diseases that we didn’t anticipate,” she said. “I think it’s important to shine a light not only on our unruly human appetites but also on the beautiful impulse we humans have to conserve and restore, which is the impulse that we will need to nurture and grow as a society if we want special wild animals like abalone to persist with us into the future.”

While doing her research, Vileisis was inspired by the passion of people who have worked to save California’s abalone.

Marine biologists and members of the White Abalone Recovery Team put out about 10,000 baby abalone in two areas off Southern California in 2019.

“At this point, it’s a bit too early to know how successful the project has been because baby abalones are tiny and hide in rock crevices,” Vileisis told CTN, noting that it takes about four years for the babies to grow large enough for researchers to find and count.

“The number of shells turning up (evidence of mortality) is not too high, and we know that there will be some years when conditions are conducive to greater success than others—SO the plan is to keep planting them out until we have enough years of success that a self-sustaining population will be restored,” she said.

Vileisis first became interested in history and environmental issues as an undergraduate at Yale, where she earned her bachelor’s degree. After completing a master’s at Utah State, she decided against an academic career and began working as an independent scholar and writer.

Her first book, Discovering the Unknown Landscape, a History of America’s Wetlands, won two national history awards. Her second book, Kitchen Literacy, How We Lost Knowledge of Where Food Comes from and Why We Need to Get It Back, was recognized by Real Simple magazine as one of “50 books that will change your life.”

Vileisis lives with her husband, Tim Palmer, a photographer, in a small town on the Pacific coast. Her other interests include whitewater boating, hiking, botanizing, beachcombing, gardening and birding. She also works as an activist focused on conservation of wild rivers, salmon and birds.

For more information about Vileisis and her books, visit: click here.